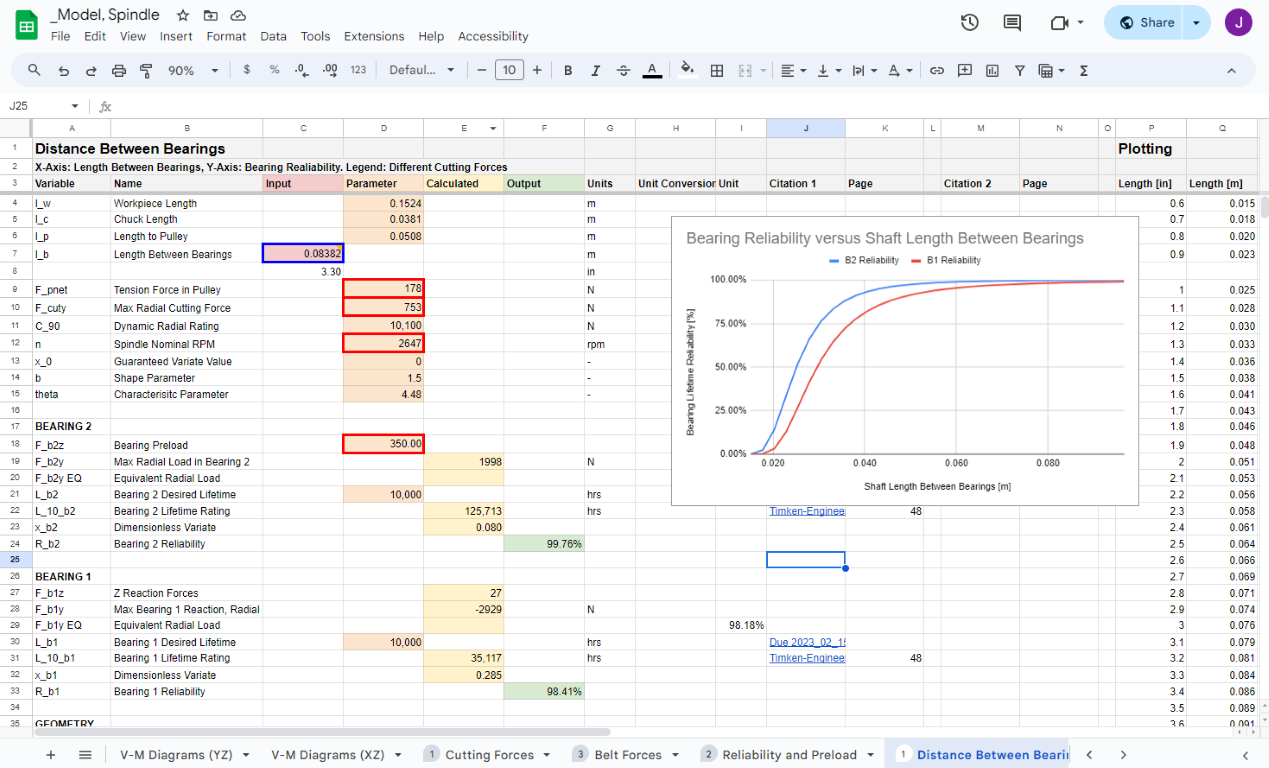

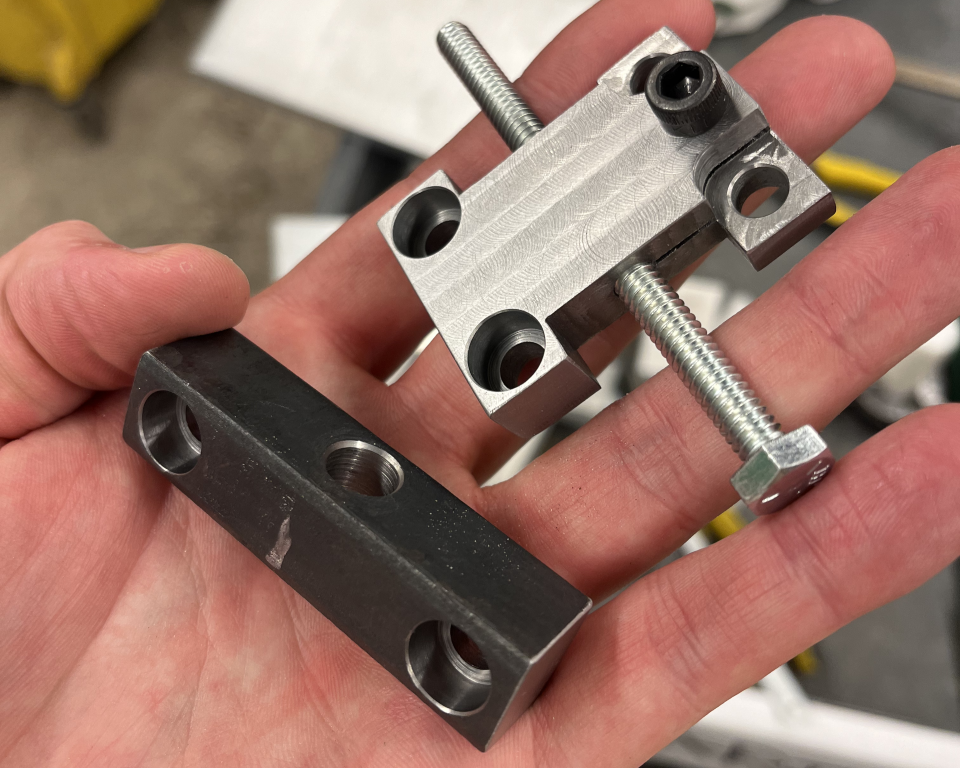

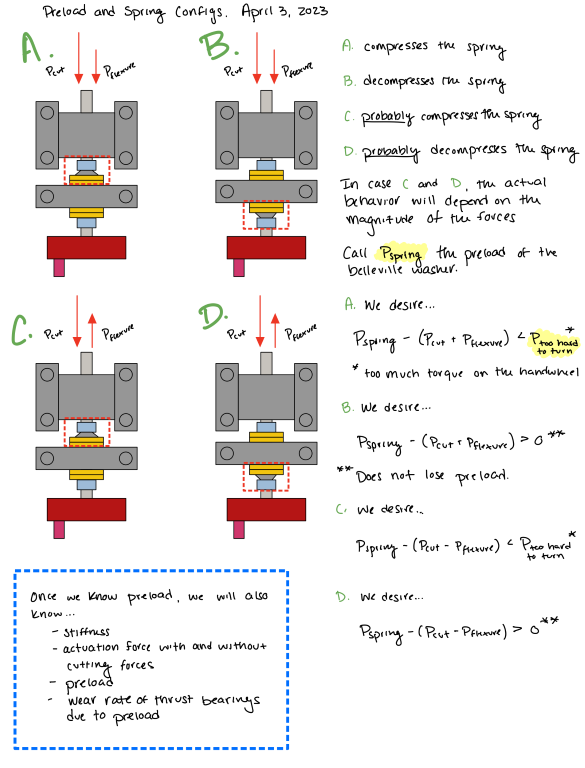

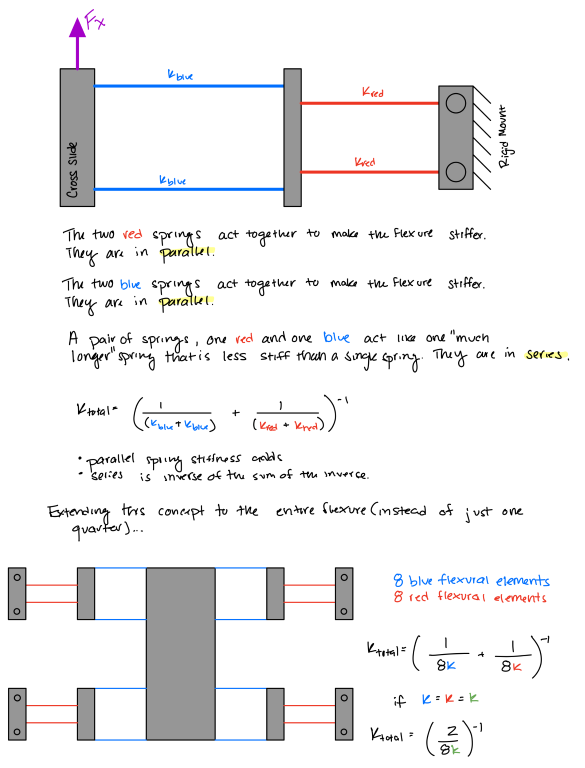

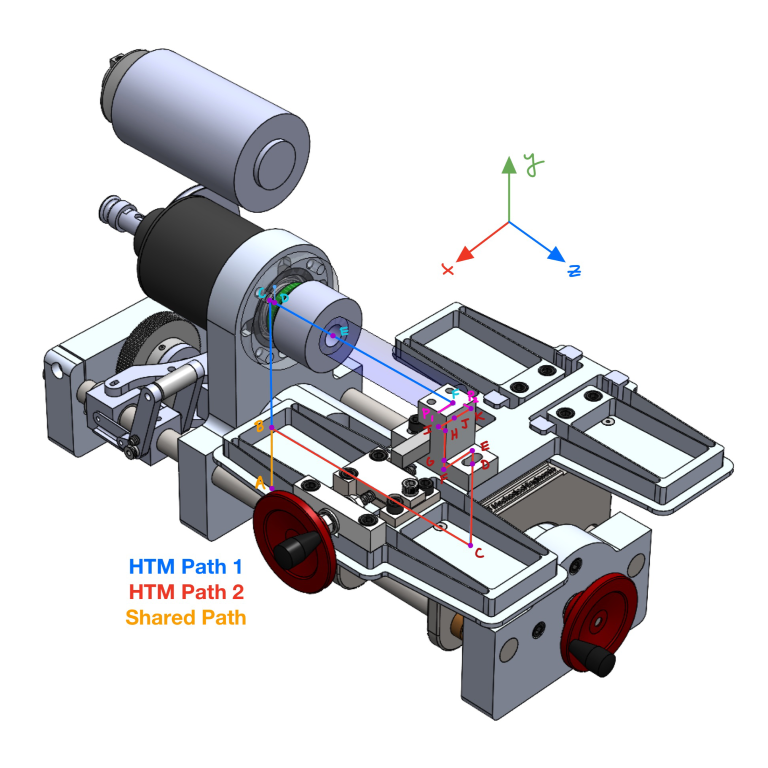

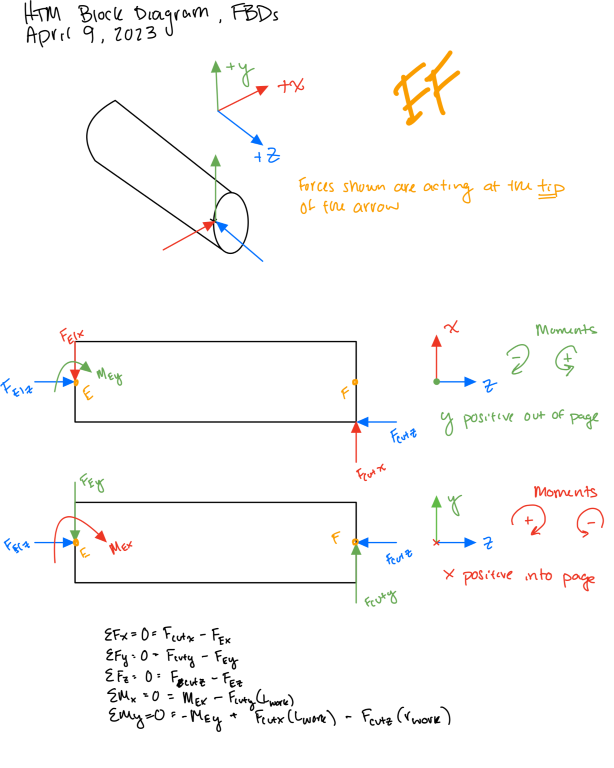

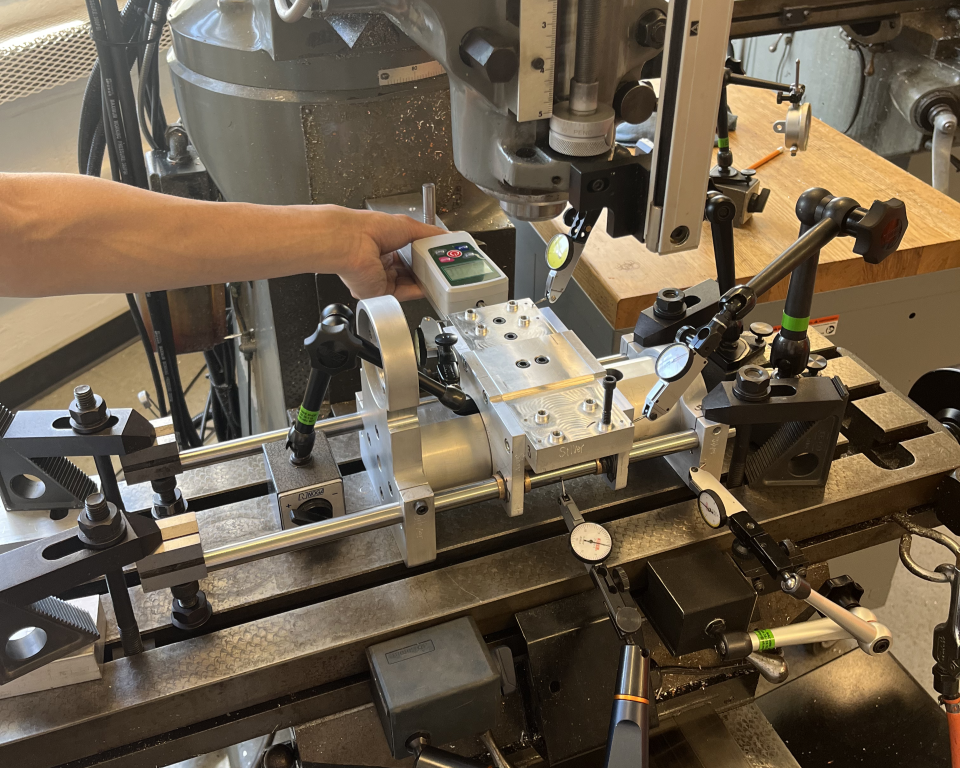

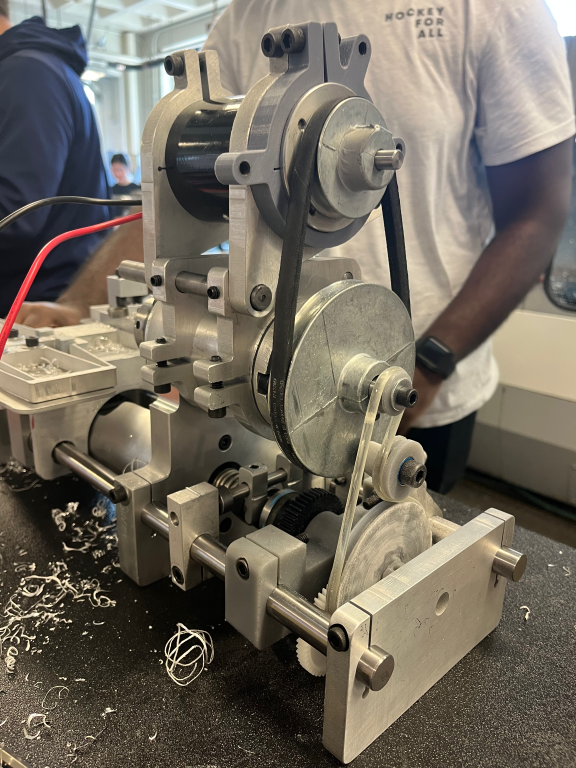

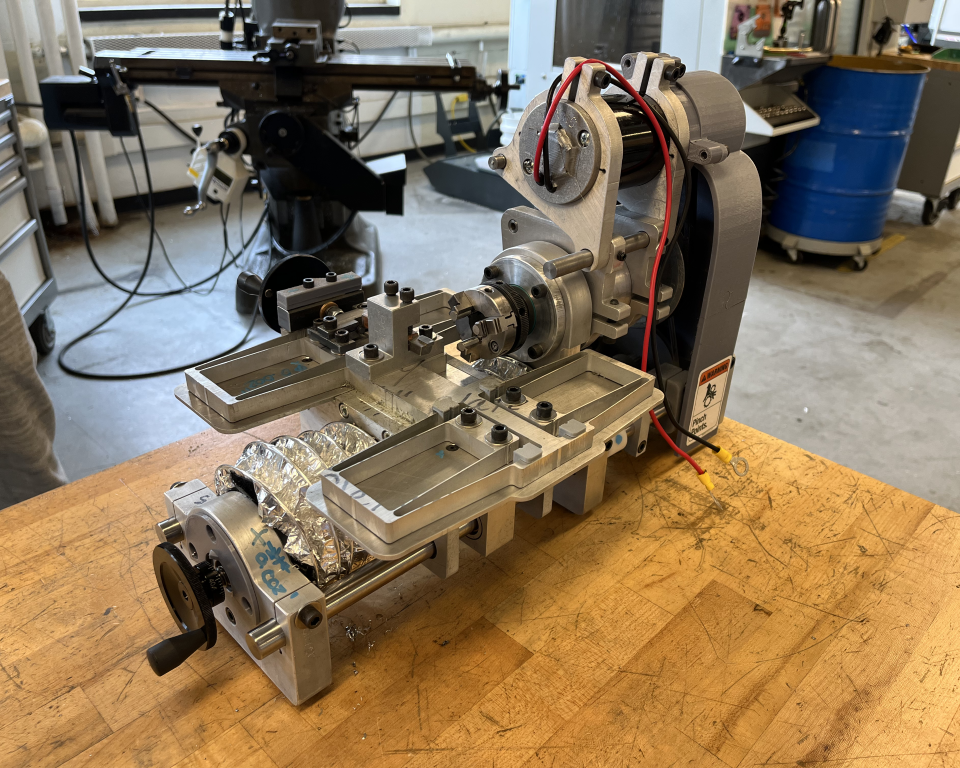

2.72: Elements of Machine Design is a notoriously challenging test of mechanical aptitude, requiring students to design and construct a desktop lathe which meets a litany of self-assigned functional requirements. For this course, I had the role of a “modeling guru,” meaning I was responsible for compiling many of the governing mathematics into scripts and spreadsheets that would inform our design decisions.

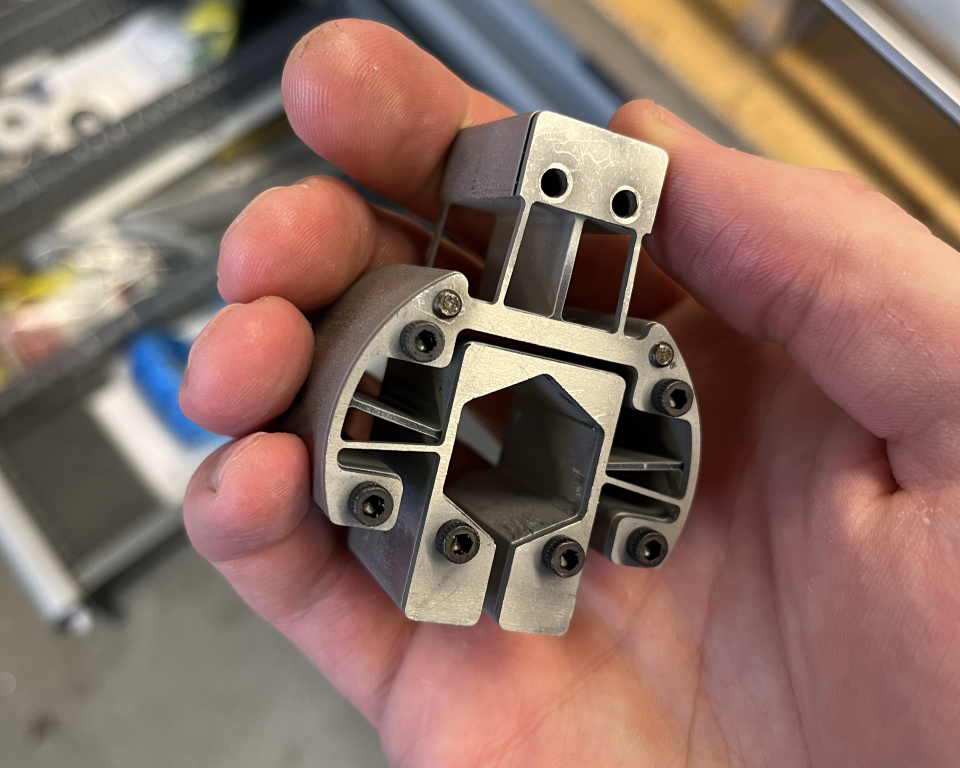

At the beginning of the semester we tear down the lathe from the previous semester and scrutinize every aspect of their design. However, this exercise only scratches the surface of what's to come later in the course as we design our own lathe.