Israel, Spring 2018

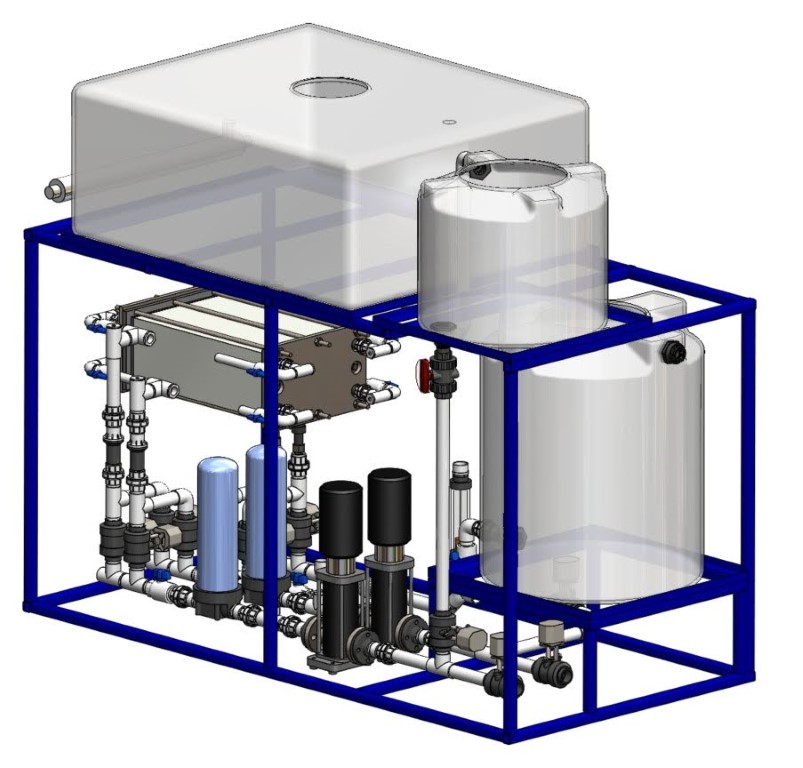

In January 2018, on just my second day working for the MIT Global Engineering and Research (GEAR) Lab, I was on a flight to Israel. Just one day before, I had started a new role as a research specialist. With my new colleagues, I'd be helping to commission one of their village-scale, desalination pilot systems its shipment into Gaza. I never could have predicted the magnitude of the challenges I would face on this trip nor could I predict how critically important this trip was to my career and my attitude toward engineering.

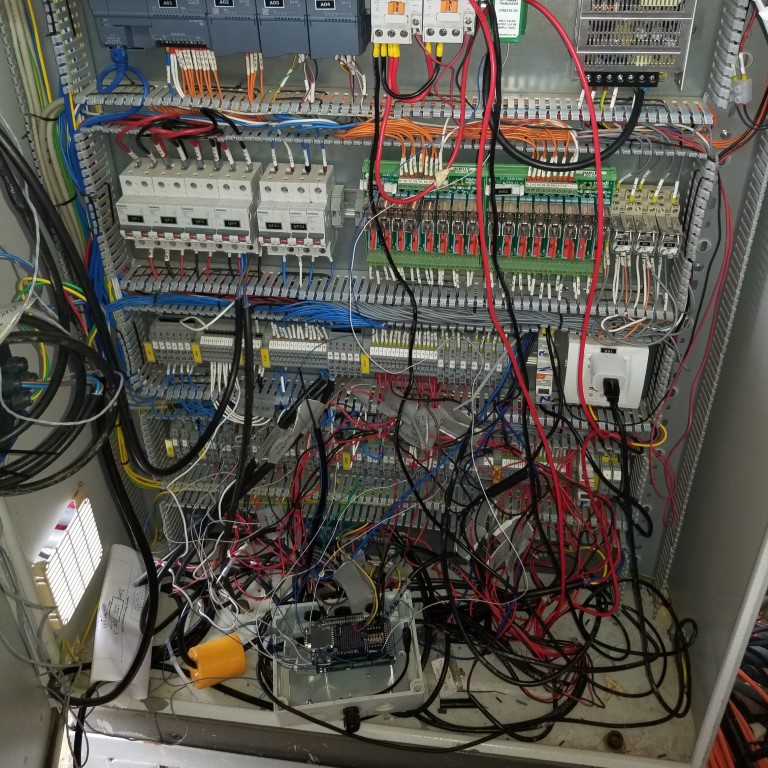

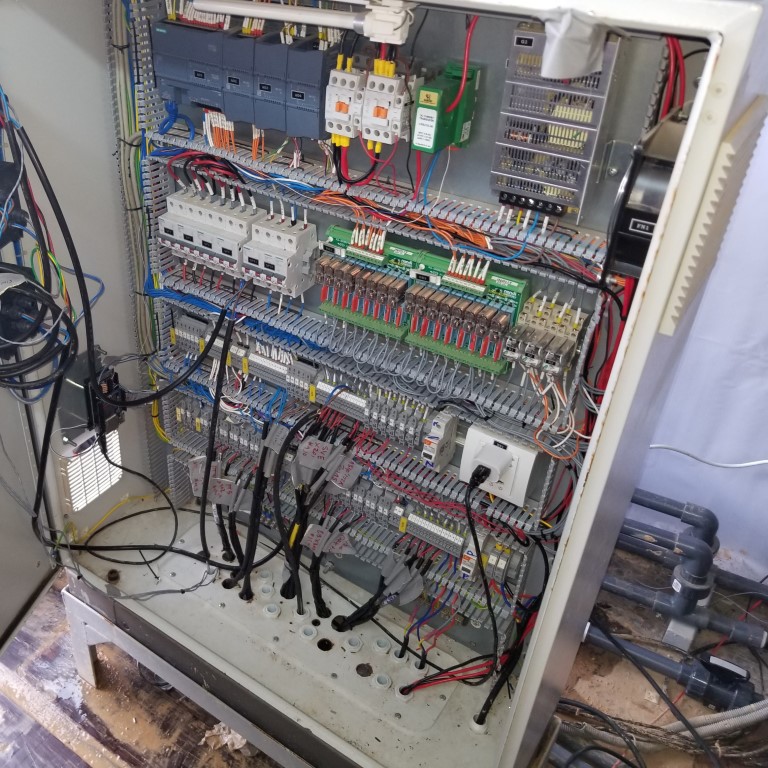

The system arrived in shambles from our partner in India - they had disassembled it almost completely. After a month of nonstop tinkering, we faked a ribbon cutting ceremony for sponsors at the United Nations. Fortunately, our sponsors were well-aware of the situation and prepared to help in any way they could. After the ribbons were cut and the banners were removed, my MIT colleagues left. I was left mostly alone, stuck in a shipping container in the desert of Israel. My task was to finalize and test the system before its shipment.